| Oration pronounced on Memorial Day, |

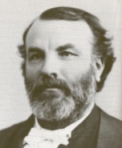

Henri Césaire Saint-PierreCe document, qui se trouve à la Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec, a été transcrit par Jacques Beaulieu, arrière-petit-fils de son auteur

ORATION Pronounced by H. C. SAINT PIERRE, Esq. Q. C ON MEMORIAL DAY, MAY 30th, 1900 IN Richford, Vermont, Before the VETERANS OF THE G. A. R.

COMMANDER AND COMRADES: Every year, upon each recurring springtime, at the opening of that cheerful season when Nature robes herself in her garment of verdure spangled with flowers of the brightest hues, when the winds are murmuring in the forest trees their songs of love, when the birds are every where filling the air with glee and happiness, there is a day when, it spite of all that which is bright and lovely around you, your thoughts are carried back to scenes of sadness and mourning. With that fidelity which becomes soldiers and friends, for the long period of thirty-four years, on the anniversary of the 30th of May, you have, each year, directed your steps towards "the silent camping ground," where our departed companions are now sleeping in their last repose, in order to offer to their graves your tribute of flowery gifts together with the renewed expression of your undying love and of your sorrow. This year, you have called upon me to join with you in the performance of this pious duty, and you have requested me to speak to you of those past events in which they and we had a common share. I thank you for this kind request. You might easily have found a more eloquent exponent of those thoughts with which, on this day, your minds are filled, but not so easily, one more loyal to the past, nor more sincere in his sympathetic remembrance of those, both dead and living, who were once his companions in arms; and if my presence amongst you on this occasion is susceptible of operating any change in your customary celebration of "Memorial Day", let that change consist simply in the fact that one brother more is added to your number. We have met today to speak together of our departed companions and to put ourselves, as it were, in communion with them. Ah! true, their lips are closed for ever and their voices can no longer be heard, but it seems to me that their spirits hovering over their tombs have followed us to this hall and are still moving amongst us. It seems to me that upon recalling to our memories the great deeds which they have achieved and the great cause which they have defended, we will, as on the days when they were fighting by our side, feel their encouraging influence. It seems to me that prompted by their secret whisperings, we will, on leaving this hall, walk away impressed with the obligation now devolving upon us, the veteran soldiers, of placing before the eyes of our children and of the growing generation, the noble examples which they have set to the world, in order that from those examples, our children may learn what degree of heroism and devotion a soldier may be led to, throught the love of his country. Comrades, what was it which during the four years of the war brought so many combatants around the flag of Washington and Franklin? Was the soil of the fatherland threatened by the undisciplined and untutered savage of the Wild West? Was it polluted by the foot of the foreign invader? Had England, France or Germany threatened with their mighty fleets the shores of the Republic, that Republic which one of its presidents has proclaimed "the sacred home of the American people"? - No, Comrades; the strife was between brothers. The fathers of the Country had proclaimed it as the fondamental principle of the Constitution that "all men were born free and equal", and the question at issue was whether a republic founded upon such a principle could subsist. I cannot define the question which was then at issue in terms more impressive, nor in language more eloquent than that which feel from the lips of the man who was the greatest hero of the war as well as its last martyr, the good and noble Abraham Lincoln. Leet me quote his own words pronounced on the occasion of the inauguration of the Gettysburg Cemetery, upon that battlefield where so many of our dead comrades had fallen. He said: - "Four scores and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now, we are engaged in a great civil war testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We are met to dedicate a portion of it as the final resting place of those who here gave their lives that that nation might live ... It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work that they have thus far so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from those honored dead we take increased devotion to the cause for which they, here, gave the last full measure of devotion, that we, here, resolve that the dead shall not have died in vain, that the nation shall under God have a new birth of freedom, and that the government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from the earth." What was it then, I again repeat, which brought so many combatants from so many various lands to share in the struggle for the maintenance of the Union? Oh! I am well aware the the rebellious population of the Southern States were not without friends and sympathisers, and I am not by any means surprised at the shouts of exultation which crossed the broad Atlantic ocean at the prospect of seeing the American Republic cut asunder and devided into two deadly rivals. The men who were then predicting the downfall of the Republic were crowned heads and aristocrats, who by instinct, by education and by profession are the natural enemies of the people. But if kings and aristocrats were the enemies of the American Union, "the men of the people" were not so. They felt that in the mighty struggle which was going on, there was a cause to defend which was their cause, namely, the cause of democracy; and moved by Columbia's inspiring and soul stirring national songs, from almost every quarter of the globe, hundreds and thousands hastened to rally around the glorious "stars and stripes", the sacred emblem of popular rights, in order to give a helping hand to the American boys and to fight and fall if necessary in the defence of democracy. In those days as well as now, there were in our free Canada, men of the people with strong arms and stout hearts, who did not think that they would proved disloyal to their country by giving a friendly help in the defence of the cause of the people and of humanity, and who cheerfully joined the ranks of their American brothers. I, and many others whose names are familiar to you, were among the number, Comrades. Carried away by the enthousiasm of our youth, we fought and bled for the sacred cause of the people and for the abolition of slavery; and the bloody strife once over, we returned to our homes, proud of having contributed to the triumph of freedom and to the maintenance of the government of the people, by the people and for the people. Comrades, a hundred and fourty years ago, thirteen States which then formed the nucleus of the mighty republic now called the United States of America banded together and united their strenght to lay the foundation of a government such as the world had never witnessed before. They proclaimed, as the first article of their creed, that all men were born free and that in the eyes of the law and of the constitution, any man was the equal of any other man. No privileged classes, no aristocratic distinction were admitted. The American citizen was taught to believe himself the peer of any man; and like the Roman of the olden times who could make even a king tremble by proclaiming his title of citizen of Rome, the inhabitant of the soil of the American Union was made to feel that he could command the respect of the world by being called an American citizen. "Civis Romanus sum", would proudly say the Roman in the days of the Roman Republic. With no less pride and with as much certainty to command respect, the man of the people from the American Union can in his turn say to day, "I am an American citizen." I stated, just now, that this republic was unlike any one ever known to the world at any period of time before, and history will support my assertion. Athens was a republic, but the extend of its territory was so limited that its citizens, instead of entrusting the matters of state to the calm discussion of a house of representatives, would, even in the most momentous occasions, constitute themselves into a deliberative council, and in boisterous assemblies, they would pronounce upon the most vital question concerning the welfare of their country. Rome was the mightiest republic of antiquity; but note the wide difference between its government and that of the American Republic: One third of its population was composed of patrician families who would look down with contempt upon their plebeian countrymen. The power of government was centered into the aristocratic Senate, the authority of which ruled supreme. The rest of the people sought their protection against oppression in the use of the right of "veto" which was exercised by their "tribunes," whom they elected every year. But history tells us that this protection was indeed but a very weak and slender barrier with which to stem the tide of the ever increasing influence of the proud and mighty senators. There was no equality there. The Patricians were the masters and the Plebeians the slaves. It may not be without some interest for you to know that at the epoch when the city had reached the zenith of its power and of its glory, under the first emperors, Rome had a population of nearly six million inhabitants, and that out of that large aggregation of human beings, no less than four millions, mostly all white, were slaves. Every menial servant was a slave: The "domestic" servant, (thus called from the word "domus" which means the house, the home), formed part of the furnishing of the house and were generally bought and sold along with it; actors on the stage, musicians, painters, artists and even notaries-public whom they called "Tabelliones" were slaves and constituted a portion of the estate of some wealthy patrician families. Lawyers and doctors however were an exception to the rule. None but free men (liberati) could be admitted to the practice of medecine or to the privilege of pleading in the forum. Hence the name "liberal professions" given to the practice of the law or that of medecine. I need not press the comparison any further. Venice in the middle ages was also a Republic, and for a considerable period of time, was proclaimed the Queen of the Adriatic sea, but its government was an oligarchy composed of men selected among the members of the nobility. The people had neither voice nor influence in the affairs of public administration. To America was reserved the honor of being the cradle of the first exclusively democratic government which ever existed in the world. The birth place of Democracy is America. Any man born under its flag, no matter if he sprung from the poorest or humblest classes of society has an equal right with the wealthiest, to aspire to the highest and proudest station in the land. Here, no titled scape-grace, no aristocratic idiot can expect to command influence nor even respect, by the mere virtue of his birth or of his associations; but Grant "the tanner" became the commanding general of an army numbering over one million of men, and Abraham Lincoln a toiler of the soil, the "rail splitter" as his ennemies would sometimes call him in derision, became the president of a mighty nation. The former proved himself a general worthy of being compared to the most illustrious both in ancient and modern times and the second was proclaimed the greatest man of the age. It must be admitted however that the moment the American people were left at liberty to chose their own form of government, the change was one which was easily brought about. Their fathers had hailed from old England, that classic land of liberty, where from their very childhood, the notion had been impressed upon their minds that "No Britton should ever be slave." The evolution therefore from a popular government tempered by the authority of a King "who reigns but does not govern," and that of House of Lord which may for a time check, but never absolutely opposes the popular will, as the system existed in England, the evolution, I say from that system to a purely democratic government without a King and without privileged classes, became an easy one and was operated almost without effort. The new form of Government had not subsisted many years but it excited the admiration of the world, and very soon changes and reforms were demanded and insisted upon by every nation in Europe. I have just said that the evolution from a monarchical to a republican form of government in America had been an easy one in the midst of your puritan ancestors; it was far from being so however among the nations of the old world who wished to follow their example, as I will now show you. Fourteen years had hardly elapsed from the date of the signing of the American constitution, when the struggle began, and when the most sweeping revolution ever recorded in history broke out in the old world. Prompted by the example set by the American people, Democracy which thus far had been enslaved in the old continent resolved to assert her rights. Like the athlete of old in the Olympian games, she rose in her might, bearing her arms for the deadly conflict about to be engaged between herself on the one side and the Crown Heads and the priviledged classes on the other. France became the battlefield wherein the question was to be decided whether it was true, as had been affirmed by the fathers of the American Constitution, that "every man was born free and the equal of any other man," or whether it was not better that three-fourths of the population should be the slaves of the other fourth. Comrades, whilst I am thus speaking of the march and progress of Democracy throughout the world, allow me to make a short digression and to put before your eyes a small sketch of what the condition of France was before the great revolution of 1789, which swept away the ancient order of things. You will then judge for yourselves whether we were right in fighting for the maintenance of the republic and of the great principle of the sovereignty of the people upon which it was made to rest. King Louis XVI was sitting upon the throne of France wearing a crown and weilding absolute sway over the nation by the authority of what he claimed to be the divine rights of Kings. "The whole of the territory of the kingdom" says the historian Chambers "could be divided into three distinct parts: one third was owned by the nobility and another third was the property of the clergy, and both the nobility and the clergy were exempted from taxation." Judge from this statement of the condition of the mass of the people, the toilers of the soil, who alone had to bear the whole burden of taxation. Imposts were put not only upon such commodities as in America are considered fit subjects for taxation, but upon every thing which is of primary necessity to life. Taxes were imposed upon every article of food, even upon salt. The peasant had to pay a tax for every animal he possessed, and if he desired to gratify his luxury to the extend of putting up a glass window to his humble cottage, he had to pay a tax for it. Direct and indirect taxation were both resorted to. The direct taxes were collected in a manner which made them particularly oppressive and odious. In each circumscription, they were sold in advance to the highest bidder at public auction and bought by men who took the name of "King's farmers general," who, in turn, would collect them from the people for their own personal profit with unmerciful greediness. Intermarriages between the nobility and the people were frowned down and looked upon as stains upon the former, and the unfortunate scion of noble birth who would marry a maiden of the people was cast away from his family as having brought shame and disgrace upon the escucheon of his noble sires. At a pinch, he could make her his mistress however. To bring shame and dishonor upon the maiden's family was not thought to be wrong in any way; but for him to take her to his bosom as the woman of his love and the mother of his children was a crime never to be condoned. In the army no man who did not belong to the nobility, no matter how pure his patriotism or how transcendant his abilities or his genius, would ever be allowed to reach a higher rank than that of sergeant. In the navy, he had to be satisfied with remaining an ablebodied sailor. Wars of the most disastrous characters would be undertaken not for the defence of the country, nor yet for its benefit, but for some anticipated advantage in favor of the King's family connections, and in some cases, for motives still less worthy. "Through the windows of the room wherein I am now speaking," once exclaimed Mirabeau, the great orator and statesman of the revolution, in one of his eloquent outburst of indignation, "Through the windows of the room wherein I am now speaking, I see the very palace wherein a courtisan set the whole of Europe in a blaze, because a King had been too slow in picking up the glove which she had dropped on the marble floor". Generals and Admirals were frequently selected for the most important and responsible positions at the head of the army or navy, through the whymsical fancy of the King's favorite mistress; and the intrigues resorted to and the manoeuvres put into operation to conciliate the good wishes of the gracious lady were not even attempted to be conceiled from the observation of public curiosity. Officers' commissions were bought and sold to the highest bidder, no matter how wreckless or unworthy the applicant might be for the position. The son of a craftsman had no right to aspire to any higher occupation than that which had been carried on by his ancestors, and if a shoemaker the father was, shoemaker the son was bound to be. Justice was shamelessly sold or still more shamelessly influenced by the friends or favorites of the King. And to crown all, upon a secret denonciation, a citizen, sometime the father of a family, could be suddenly pounced upon and lodged in the dungeons of "La Bastille", by means of a warrant called "lettre de cachet" signed by the King, without any member of his family nor any one of his friends ever being made aware of the fate of the doomed man. Latude one of those victims of tyranny was kept for thirty years in this terrible prison. He wrote the story of his lonely life with his blood upon the wall of his dungeon. When he was released, on the storming of the Bastille by the people of Paris, on the 14th of July 1789, he was found to have become insane. He was but a skeleton and a maniac, a wreck both in body and mind. Do not fancy, Comrades, that I am portraying to you a state of things such as existed during the dark ages of the world. No, I am referring to the condition of the people of France at the very eve of the breaking of the revolution, a little over one hundreed years ago. I have just given you a small sketch of the condition of the French people prior to the revolution but do not conclude thereby that this state of things was to be found only in France: Had I made the picture a little broader, I might have included within its frame, Italy, Spain, Austria, in fact the whole of Europe except England and Switzerland. Every where, the people was the slave of kings and of the nobility. Nowhere, except in the two countries just named were the lower classes allowed the least share of influence in the government of their respective countries. One day, the oppressed people of France felt that they could bear oppression no longer: goaded to desperation France rose in a state of frenzy; the chains were snapped from her writs; she wrenched from the hands of her oppressors the weapons which they had so long wielded for her destruction; she picked up the sword yet crimsoned with the blood of her children, and with all the power that madness inspired by fury and revenge can instill in the arms of one who has long been suffering, she struck to the right and to the left. Under her mightly blows, the "Bastille" the hated prison crumbled down to pieces; the King, in spite of his divine right, feel never to rise again and the blood of the nobility, that headstrong nobility, which, even then, would not consent to yield an inch of its self asserted priviledges, filled the gutters of Paris. The crowned heads of Europe took alarm and trembled on their thrones at the sight of the rise of Democracy in France. They combined together to crush it under their feet; but the vigorous French Republic was equal to the task, and no less than fourteen armies organized by the "Committee of Public Safety," rushed to the front in defence of the cause of Democracy and of the soil of the Republic. At the heads of those armies, we find men, who, like Grant, Sheridan, Thomas and scores of others in America, had sprung from the humblest among the people: We find Napoleon Bonaparte, the son of a lawyer, Berthier a sergeant and Bessière, a private in the King's body guards. We find Soult, Suchet, Victor, Lefebvre, Loison, Massena, all former privates in the King's army. We find Ney, the bravest of the brave, the son of a poor tradesman of Saare-Louis, in Lorraine, and Murat the dashing cavalry leader, who always charged at the head of his troops waiving a whip in his hand in lieu of a sword, the son of an inn-keeper. Comrades, I am not ignorant of the fact that Democracy in France was conquered for a time, but whilst regretting that misfortune, yet there is a certain satisfaction in knowing that it only yielded to the glittering charms of military glory. But look around you and watch throughout the world the mighty triumph secured by the American and French revolutions. The great principle laid down by the signers of the declaration of independance in America and by the authors of the declaration of "the rights of man" in France, to the effect that the people should be governed by the people and for the people was accepted by every civilized country, the world over; and in our days, whether on the continent of America or on that of Europe, there is hardly a civilized nation to be found in which the government of the country is not carried on after the pattern set to them by the American Republic, that is to say, by means of a house of assembly composed of representatives chosen and elected by the people. Some might perhaps say that the secession of the Southern States from the Union and the disruption of the Republic, had it taken place, did not necessarily entail the downfall of Democracy in America and that the dark forbodings of the late President Lincoln were inspired more by patriotic fears than by any actual danger. Comrades, no one can tell what direful results might not have flowed from the breaking up of the Union. If the principle had once been accepted that the pretented States Rights should be allowed to prevail, no one can affirm that some day or other, under the flimsyest pretext, the Western States might not have followed the evil example set to them by the Southern Confederacy. "A house divided against itself cannot stand," say the Holy Writs, and no one could have foretold what the final fate of Democracy might have been in all those small republics shorn of that strength, and of that mutual confidence which resulted from their being banded together by the same principle of government and protected by the same flag. The motto of the United States is "United We stand, divided We fall." In inscribing this motto upon the escucheon of the Republic, the fathers of the constitution intended thereby to give the future generations in America a wise and timely warning of what would be the fate of their country, in the event of their ever being tempted to break the sacred pledge which had bound the inhabitants of the whole territory of the United States into one single community. Who can say but some conquerors from across the sea might not have invaded those divided states, in order to crush under foot the work of the fathers of the Republic and put an end once and for ever to the hated democratic government? Have you forgotten that thirty-six years ago, precisely during the very period of time when the war of secession was at its highest pitch, a foreign army invaded Mexico, and that a foreign potentate succeeded in subverting its democratic and republican institutions? Fortunately, the people of the Mexican Republic soon awoke to their rights, and led by their republican President, they succeeded in repelling the invaders. The imperial throne erected upon the very spot where the presidential chair had stood before was overturned, and Emperor Maximilian paid with his life the audacious enterprise of attempting to become the master of a free people. But, what might not have happened, had the Mexican Republic been divided against itself or broken up by partial secessions? President Lincoln was right therefore: In defending the Union we were defending our cause, the cause of the people, the cause of Democracy in America. We fought for the Union in order that the great and honorable title of American Citizen should be preserved and respected. We fought for the Union in order that in this, the land of the worker and of the toiler, the man of the people might continue to feel that there is more nobility in honest labor than in glittering titles. We fought for the cause of Democracy, in order that no man should one day presume to deprive us of our liberty or dare to thrust any one of us into a dongeon withoput any just cause for so doing, and without due process of law. We fought for the cause of Democracy, in order that our virtuous mothers, wives, daughters and sisters should not be looked down upon with the lips of contempt by an insolent courtisan, who would believe herself a superior being from the fact that she happened to have been born of patrician parentage. And finally, as president Lincoln so well expressed it, we fought even under the very shadow of death so that the nation might live. This is what brought so many helping hands and devoted hearts around the flag of Washington. But, aside from the cause of Democracy, there was another one of no less importance which formed part of the issues to be finally determined by the war in which we fought thirty-five years ago: in fact the two questions were so blended together that they may be said to have formed but one in reality. I am alluding to the liberation of the slaves in the Southern States. Slavery, as you are aware, was preexistant in the Southern States to the foundation of the Republic. The complexed problems which beset the path of the framers of the constitution were by far too numerous for them to undertake the settlement of the vexed question of slavery with one stroke of the pen. They felt contented with affirming the broad principle that in the new born Republic "every man should be free," and they left to the initiative of each state government the care of eradicating the evil as time went on and circumstances would permit. Unfortunately the hopes expressed then were not realised, and slavery instead of gradually disappearing, as had been anticipated, went on rapidly on the increase, until at last, various attempts were made to introduce it into the Western States. You know the sequel: the election of President Lincoln wich took place directly on that issue, the refusal of the Slave States to submit to the will of the people and repudiating Mr. Lincoln as their president, the secession of the Southern States, the election of Mr. Jefferson Davis at the head of the Southern Confederacy, the attack upon fort Sumter, the proclamation of independance by the Southern States and the war. Comrades at the same time as we were defending the cause of the Union, we also defended that of humanity itself by fighting for the abolition of slavery. Is there any one of us who ever regretted it? A man may sell his labor, his ability, his skill, his learning, but he cannot sell his person. Man is a creature of God, born to do his will; he cannot withdraw himself from God's dominion and substitute to that dominion that of man, by becoming enslaved under the absolute power of another. No one has the right to become the absolute master of another man, no matter what country the latter hails from, no matter what sun may have darken his face. Have you ever travelled through the Southern States before the war? Have you ever visited a slave market? If you have once been a witness of what was being done there, did you not feel your very temples throb with the deepest indignation at the sight of the husband torn from his wife's embrace, the father from his son, the mother from her children, and even from her infant baby? To a man harboring in his breast the least feeling of respect for humanity, could any sight be more shocking, more revolting, than that offered to his gaze by those purchasers of human beings patting with their lascivious hands the forms and flesh of a young woman, just as they would do those of a beast of burden? My blood boils at the very thought. Methinks I am present at such a scene with my old comrades of the 76th, N. Y. Methinks I hear my brave captain shouting to us; "Boys are we going to allow such abominations to take place before our very eyes? Are we barbarians, savages or christian soldiers? Do you not see that father taken away from his weeping children? Do you not notice the yound child torn from the arms of his distracted mother? Hark - Do you not hear their screams, their desperate appeals for help? Is there no hope for them? Are we to remain idle spectators of such degrading scenes? Forward boys, sweep away all that heartless crowd, seize those weeping children and bring them back to their broken hearted parents." With what alacrity would not the order have been obeyed! Who is the coward among us who would not have risked a thousand lives for the sacred cause of pity and humanity? Had I been there with a sword in hand and fifty Camerons by, That day, through Dunedin's streets had pealed the slogan cry, Not all their troops of trampling horse, nor might of mailed men, Not all the rebels in the South had born us backards then. Comrades, if ever war was waged for the sole and unique purpose of slaughtering men and destroying property, it would be one of the worst crimes that could disgrace humanity. War is no doubt a terrible evil, but there are times when it becomes a necessary evil. It can only be justified by the supreme law of self defence. Men will kill other men to save their own lives or to save the community in which they live from serious inroad or from total destruction. The unjustified attack having once been repelled or the power of the enemy having been crushed down and rendered incapable of doing any further harm, all hostility and all agression must cease. The deadly strife once o'er Then curls the smoke of peace. So it was with us. The moment that Lee and Johnston surrendered their swords, from that same moment the work of peace and the restoration began. But what became of the immense army of over one million men? They gave to the world this grand lesson that the citizen of a republic may become the defender of his country without at any time abdicating his title of citizen, nor shirking the duties and obligations which that title entails upon him. They followed the example and direction which were given them by their chieftains. I cannot here resist the temptation (even at the risk of detaining you for a few moments longer than I desired) of giving you the last words which feel from the lips of General Sherman just thirty five years ago on this very anniversary of the month of May in his farewell address to his army: "To such, said he, as will remain in the military service, your general need only remind you that success in the past, was due to hard work and discipline and that these are equally important in the future. To such as go home, he will only say that our favored country is so grand, so extensive, so diversified in climate, soil and production that every man may surely find a home and occupation suited to his taste, and none should yield to the national impotance sure to result from our past life of excitement and adventure. "Your general now bids you all farewell, with the full belief that, as in war you have been good soldiers, so in peace you will be good citizens; and if unfortunately new war should arise in the country, Sherman's army will be the first to buckle on the old armor and come forth to defend and maintain the Government of our inheritance and choice." With the same respect and the same veneration with which dutiful children will receive the last wishes of a dying father, you have treasured up those words in your heart, and you have realised to the letter the hope expressed by the great soldier: As you had been good soldiers, so you became good citizens. You have even done more than had been expected of you: You have perpetuated what is good in war by maintaining between the members of this immense army, that spirit of brotherhood which had its origin in the baptism of blood and fire which we all received on the battlefield; and in order the better to insure the maintenance of that brotherhood the strength and power of which no one can well understand who has not been a soldier, you have organized "the Grand Army of the Republic", an association based upon the three cardinal virtues of loyalty, fraternity and charity, which has, every where, covered the land with its good work and which is now perpetuating itself in the new generation, the children of the veteran soldiers. In your ranks you have admitted that admirable association of women, known as The Relieved Corps, which has done so much during the dark days of the war for the assistance of the sick and wounded and whose benevolence has often reached even to the very heart of those dreadful prisons wherein so many of us had to face sickness, starvation and death. In the Sons of Veterans, the Government of the Republic has found ready material for its late war with Spain, and at the first sound of the trumpet a generation of young men bred in the school of patriotism, and eager to serve their country as their fathers had done, responded with alacrity and zeal to the call. This, (and you may well boast of it) has been the natural result of your work in perpetuating the good instincts which the lessons and the associations of the war had instilled into your own hearts. Comrades, whilst we may on this anniversary bring back to our recollection with a feeling of pride what the army of the war of the Rebellion has done for the country, let us not forget that this day is more particularly dedicated to our dead companions. Let our first as well as our last thoughts, today, be for them. - Let our words of praise and our expressions of gratitude be for all and every one of them. Let it be for our dead comrades of the armies of the north, of the south, of the east and of the west. - Let us remember with a heart swelling with gratitude and pride all those great names which the hand of History has already engraved upon the pedestal of the statue of Liberty: Grant, Sherman, Mead, Sheridan, Dolgreen, Dupont and a score of others who have lead us to Victory. Let us give a word of praise to that immortal "Vermont Brigade," whose timely assistance secured the victory to our arms at Gettysburg and whose distinguished gallantry has been conspicuous upon so many battlefields. But above all, let us give expression to our deepest gratitude in favor of those humble combatants who sacrified all, even their names together with their lives, upon the altar of their country. Ah! no one can speak more knowingly than I of their self-sacrifice and of their devotion to their country. In those dreadful prisons of the South where more than one year of my life was spent, I have seen hundreds of them die without a murmur, whose names after their death, was neither recorded, nor even cared about. May their remains rest in peace, and their souls be blessed for ever. They have died, but it was for their country's cause, and if, as I believe, it be true that there is somewhere behond the grave a place of rest and reward for the good and the brave; upon this day, there must be added to their happiness some particular gratification in knowing that their sacrifice and their devotion have not been forgotten, and that once a year there is throughout the land a day set apart to honor their memory and when the universal gratitude of a great nation proclaims it loudly that they, indeed, have not died in vain. |

Jacques Beaulieu

beajac@videotron

Révisé le 22 juillet 2019

Ce site a été visité 50395167 fois

depuis le 9 mai 2004